No products in the cart.

WATER SUTRAS— THE BAOLIS OF DELHI

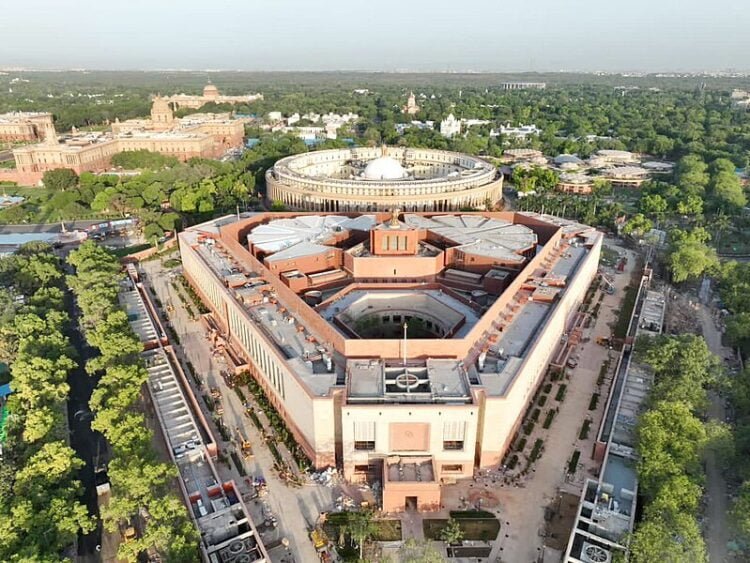

Delhi- Structures of Utility and Beauty from Antiquity

By Ranee Sahaney

With temperatures slowly climbing the charts heralding the onset of summer our thoughts wing out to Delhi’s water heritage. Given its proximity to Rajasthan, memories of the searing loo, water shortages and limp gardens rush in, reminding us of how past rulers of ancient Delhi, like in Rajasthan, set in place solid water harvesting structures to counter the dearth of potable water in the summer months.

What adds to the city’s woes is that the growing populace, which is rapidly bursting its seams, has played havoc with the water table as have the vagaries of the weather gods.

Marvels of human endeavour, baolis (stepwells) of yesteryear capture our imagination for their utilitarian purpose as much as do the engineering and even architectural wonders of some.

Stepwells, familiar to local communities as baori, bawdi, vav, kund, vapi, sagar, in Delhi have certainly paid a heavy price for the neglect they have suffered, ever since the British unleashed their modernization agenda around the 19th century, which willy nilly overran long standing local traditions on many counts. Many of these water bodies fell into disuse, being considered unhygienic, and were being rapidly substituted by taps and handpumps, particularly in the rural landscapes.

The conservation of rain water for drinking and agriculture, for the year-round supply, was embedded in the socio-economic ethos of the villagers and the farming communities scattered along the outskirts of ancient Delhi. What silently creeps into the immersive experiences of visitors is that stepwells also served as an important socio-cultural and religious hub for the community.

Delhi, on the cusp of the last century, was home to over 100 stepwells. Not even a handful of those remain today. These used to be fed by rainwater, and, depending on their location, were supplemented by water from underground springs. The concerns of climate change have thrown the gauntlet down for local administrations to revisit the old stepwells like Agrasen ki Baoli, Gandhak ki Baoli, Rajon ki Baoli, the baoli at Purana Qila, Nizamuddin baoli, and the baoli at Firoz Shah Kotla— compelling them to revive their traditional engineering works, as much as to preserve their architectural beauty.

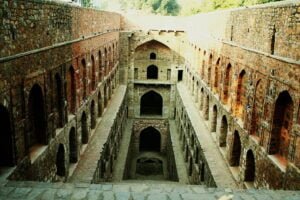

Agrasen Ki Baoli

Visitors converge for insta moments, selfies and shoots on this hitherto hidden gem located on the uncrowded Hailey Road, off K G Marg, in Connaught Place. Believed to date to the epic period of the Mahabharata, as propagated by local lore, the baoli takes its name from the ruler Raja Agrasen of Agroha; the Agarwal trading community claim to be the raja’s descendants. Surrounded by a forest of sky-kissing high rises it also goes by the name of Ugrasen ki Baoli. And it’s still in pretty good shape. What you see today is said to date back to the 14th century rule of the Tughluqs. Strangely enough, its sweeping staircase of 108 steps dropping down three levels to access the cool depths of the ground water, and the collection of elegant arched niches, have somehow managed to escape the perils of the march of time.

Remnants of a small mosque with a whale-backed roof and pillars embellished at the bottom with Buddhist motifs, mark the entrance to the 60m deep and 15m wide baoli.

Local gossip claims the place is haunted by djinns! You’ll probably catch glimpses of it in Bollywood runaway hits like Sultan, Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna and Aamir Khan’s PK. Now a protected monument under the ASI it draws throngs of visitors, more so on weekends.

Feroz Shah Kotla Baoli

Distinctive for its circular structure as opposed to the more popular rectangular option for a baoli, the one at Feroz Shah Kotla Fort is a living waterbody with supply now coming from a forest of pipes connected to electrical pumps, which do service to the gardens in the fort, a popular cricket tournament venue.

Purana Qila Baoli

One of Delhi’s lesser trumpeted stepwells, this baoli, which lies in the historic ruins of the Old Fort, is remarked for its antiquity and ancient engineering. A flight of 89 steps, broken by eight landings, drops directly down to the baoli’s depth at 22 m. Built to serve the needs of the fort, the baoli can be seen near the main entrance between the Qila-i-Kuhna Mosque and the Sher Mandal pavilion.

Hazrat Nizamuddin Baoli

Located in the vicinity of the dargah of the Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin, this living baoli was built in 1321-22 CE. The saint is said to have personally overseen its construction. According to local lore the saint was the first to start its digging. He also blessed it so that anyone who drank even a single drop of its water would escape from the fire of hell. Its waters are believed to have curative powers.

It appears that its construction began around the time Delhi ruler Sultan Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq started building his new capital at Tughlakabad and ordered all other construction in the city to be stopped.

The Sultan and Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya had a falling out. On learning that work on the saint’s workers were carrying on building the baoli at Nizamuddin after dark, the furious Sultan stopped the sale of oil for lamps. To counter this move Nizamuddin Auliya worked a miracle by which the water in the baoli turned into oil for the lamps, allowing the work on it to carry on unhampered.

In 2009, fortuitously, the Delhi government stepped in, in time, to protect it from further neglect and ordered its clean-up.

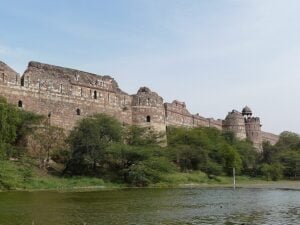

Tughlaqabad Fort Baoli

Delhi’s water problem has been an abiding companion to the city’s growth from centuries back. In the 14th century Gyas-ud-din-Tughlaq built as many as 13 step wells, but only two survived in Tughlakabad. A falling out between the ruler and the Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, resulted in the saint quitting the fortress with a curse that it would never have water. The curse, Ya Rahe Gujjar, Ya Rahe Ujaad (either a shepherd tribe will live here, or it will be uninhabited), found a mark, with Tughluq being forced to abandon Tughlaqabad with his court to establish a new capital in central India; it was because of the acute water scarcity.

The baoli is remarkable for its grand architecture. Nizamuddin’s curse appears to have borne fruit even centuries on, because the fortress is now home to a large community of Gujjars! An exploration of the abandoned fort, which is in an advanced state of ruin, makes for an exciting tour. However, watch out for the monkeys!

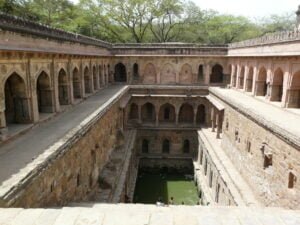

Rajon Ki Baoli

This rather ornate 3-storied stepwell, a critical source for potable water, is set amidst trees in the historic confines of Delhi’s Mehrauli Archaeological Park. It is believed to date back to the reign of Sikander Lodi.

A series of covered passages interconnect the entire expanse of the rectangular waterbody all the way down its cool depths. Back in the day the masons (rajon) living in the area would come here to gather water for their daily needs. Several rooms line the top floor. Today, the stagnant rain water at the bottom is a bright emerald green, a lovely contrast to the beautiful sand-coloured stone work.

Gandhak ki Baoli

Visitors can walk away from Rajon ki Baoli to another important baoli, just 400 m away. The gandhak, or sulphur in the water from the spring which was its source, inspired the name of this 5-tiered baoli. The stepwell offers a cool retreat from the punishing heat of the summer for the local community. Local kids still jump in for a swim ignoring the stink of the sulphur. Monsoon showers also raise the level of the water in the baoli to this day.

The baoli was built in 1230 by Shams-ud-Din Iltutmish, a general in the employ of Qutub-uddin- Aibak after whose death in Lahore, he became the first Islamic sultan to establish Delhi as an imperial capital; Iltutmish is regarded as the founder of the Delhi Sultanate.

Delhi was undergoing an acute water shortage at the time when Iltutmish visited the Sufi saint Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, living in the area. Shocked to learn that the saint was unable to even have a bath, Iltutmish decided to commission this baoli.

The Gandhak Ki Baoli, has seen some revival after the desilting that kicked into place back in 2016.

The baolis from the past have important lessons for us citizens of the 21st century. They have shown us the way to amplify sustainable solutions for water scarcity through rigorous water conservation efforts. As responsible citizens, each one of us, through efficiency and sufficiency measures — can make a difference.

Photo Credit to Delhi Tourism & Wiki commons