No products in the cart.

The Culinary Delights of Gujarat

Flavors of Gujarat: A Culinary Odyssey Through Delicious Gujarati Cuisine

Food of Gujarat

It’s evident that Gujarat’s culinary landscape is deeply rooted in its diverse history and cultural influences. The confluence of various ruling dynasties and the region’s mercantile heritage has led to a unique blend of flavors and dishes that extend far beyond the stereotypical portrayal in Bollywood. Despite its expansive coastline, the Jain influence has played a significant role in maintaining Gujarat’s predominantly vegetarian cuisine, highlighting the fascinating interplay between religious beliefs and gastronomic practices. From the richness of Mughlai influences to the simplicity of traditional Jain fare, Gujarat’s cuisine is a testament to its cultural tapestry and culinary ingenuity.

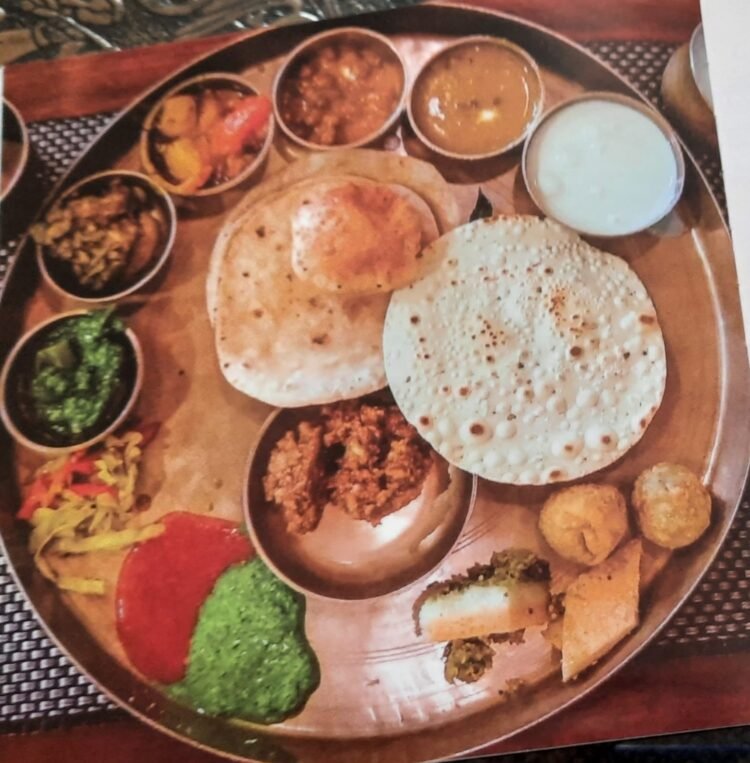

A typical meal comprises rotli (a flat bread), dal or kadhi, shaak (a dry or gravy based vegetable preparation), kathol (a preparation made from pulses or whole beans), farsan (a snack item) and rice. Many Gujarati dishes are a combination of sweet, salty, and spicy flavours. Of course, no Gu- jarati meal is complete without an array of condiments and unless it’s rounded off with a sweet dish.

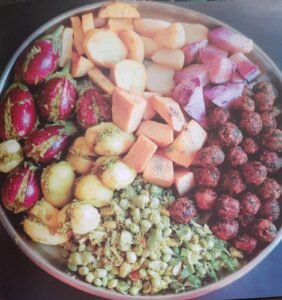

Some dishes require special utensils in their making, for example: Undhiyu is prepared in a clay pot called matla. Layers of green beans, plantains, purple yam, muthia are put in the earthen pot along with green garlic, carom and grated coconut. The matla is then hung upside down and fired. The slow cooking lends the vegetables a distinct, smoky flavour.

The popular ganthiya is traditionally made by pressing the besan dough softly but firmly against the mesh of a large pan-like strainer, over boiling oil. Nowadays, one can head to the nearest store and buy an appli- ance which is equipped with various options in which both ganthiya and sev can be made. Dhokla is made in a steamer similar to that of a idli/momo maker.

Khichdi

India is bursting with a variety of choices when it comes to meal options, but if there’s one dish that’s integral to the entire country, 1 it’s the humble khichdi. The one-pot meal is tasty, wholesome, easy to digest – and can be made in a jiffy.

This rice-and-lentil combination has been a part of India’s culinary history for eons. The word khichdi is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘khicca’, which translates to ‘a dish made with rice and pulses’. Ancient In- dian literature mentions the krusaranna, an early khichdi that included curd and sesame seeds. It has continued to please palates across India since then.

In the 14th century, Ibn Batuta, the famous Moroccan traveller who visited India, famously penned down: “Munj (moong) is boiled with rice, then buttered and eaten. This is what they call Kishri, and, on this, they breakfast every day.”

The humble dish was written about by Afanasiy Nikitin, a Russian adventurer who travelled to the Indian subcontinent in the 15th century. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a French traveller who visited India six times during the 1600s, also wrote about the popu- larity of khichdi, a dish made of green lentils, rice, and ghee, as a popular evening meal.

The Ain-i-Akbari, a document written by Mughal Emperor Akbar’s vizier Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak in the 16th century, mentions the recipe for khichdi, offering seven varia- tions. And who doesn’t know the story of Akbar, Birbal, and the pot of khichdi?

FLAVOURS OF GUJARAT

Food historian Mohsina Mukadam writes that khichdi is considered “one of the most ancient foods in India, yet one that has hardly changed”. The Mughal emperors also loved their khichdi. “There are many references to Akbar’s penchant for khichdi prepared with equal measurements of rice, lentils, and ghee.” ac- cording to Sohail Hashmi, a Delhi-based historian.

Jahangir liked his lazee- zan spicy and dotted with pistachios and raisins, while Aurangzeb had a particular liking for the Alamgiri Khichdi, which included fish and boiled eggs.

Aurangzeb’s version was picked up by the British who went on to take the recipe home as the Kedgeree, a much-loved op- tion for breakfast or brunch. In fact, even today, Queen Elizabeth and her family have a standard menu for breakfast on the day after Christmas: a big bowl of the anglicised version of khichdi.

In India, khichdi goes by different names in different states. Every region has its own take – from Bisibele Bhaat in Karna- taka to Khichuri in West Bengal and Pongal in Tamil Nadu, Garhwali Khichdi in Uttara- khand, Balace in Himachal to Khichda in

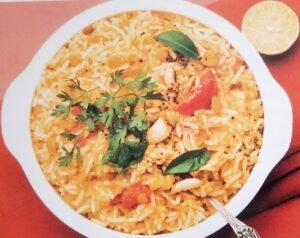

Hyderabad, it is the ultimate comfort food. In Gujarat, khichdi is a huge favourite: most families enjoy it as the evening meal at least once a week (if not more), and it is easily available in restaurants and dhabas, and for takeaway. The dish, believed to also been consumed regularly by Sultan Ahmed Shah I, the founder of Ahmedabad, is relished with Gujarati kadhi, a thin, sweet, sour, and spicy yogurt-based gravy. Sides like papad, home-made athanu (pickle), and a curried vegetable elevate this humble dish to a meal sfit for a king.

Moong Dal ni Khichdi: The most basic khichdi is cooked in Gujarati homes at least once a week. Just pressure-cook yellow moong dal and rice with turmeric,

salt, and a generous helping of ghee, and you are ready to put a no-fuss meal on the table. According to Ayurveda, moong dal is tridoshic in nature, and can balance all the three doshas-vatta, pitta, and kapha – in the body. The light and nourishing khichdi is commonly eaten with a thin kadhi, a spiced besan-and-buttermilk soup or doodhi/ringan no shak (curried bottle gourd/brinjal). Ac- companiments like papad and a pickle or two are recommended. Variants use sabut moong and unskinned split moong dal with instead of the yellow moong dal.

Fada ni Khichdi: While most khichdi recipes call for the use of some dal, this vari- ant uses broken wheat better known as dalia in Hindi and fada in Gujarati. Cracked wheat combines with yellow moong dal, vegetables such as carrots, green beans, and more, and the ubiquitous garam masala to create the perfect comfort meal. It can be slightly soupy or grainy – depending on your taste buds. This variant is extremely nu- tritious and often recommended for diabetics and weight-watchers.

Swaminarayan Khichdi: Such is the popularity of the khichdi served as prasad in Swaminarayan temples that it’s also offered in their Premvati restaurants and is one of the top-selling items. A medley of rice, tuver dal, and vegetables, this subtly spiced semi- solid khichdi is laced with ghee and served with dollops of creamy yogurt.

Badshahi Khichdi: It may sound grand, but this khichdi is extremely simple and basic. The tuver dal ni khichdi is cooked

to a semisolid consistency and then topped with a spicy potato curry. Garnished with freshly chopped coriander and served with a slice of lemon, this is a meal that, despite its humble origins, is sure to make you feel like a royal.

Ek Toap na Dal Bhaat: Think of this as the Gujarati version of the pulao. But unlike most pulao recipes that put together an assortment of rice and veggies, this spiced rice dish marries rice and dal with stuffed vegetables. Brinjals, potatoes, and onions are stuffed with a unique spice mix that includes grated coconut, dhania jeera powder, red chilli powder, salt, sugar, and oil, and cooked along with the rice-tuver dal mix. Served with dahi and a spicy pickle, one-pot meal. Now you can have both nutri- tion and taste on your plate!

Sabudana Khichdi

This one’s perfect for the days when you’re fasting and can’t consume rice and lentils. This khichdi isn’t just limited to Gujarat; it’s also prepared in states such as Maharashtra. Karnataka. Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajas- than. All the carb-rich recipe needs is tapi- oca pearls, chopped potatoes, and crushed roasted peanuts. When combined with a generous helping of green chillies, curry leaves, and cumin seeds, it leads to a one-pot meal that’ll leave you craving for more. Soak- ing the sabudana for just the right amount of time is key to getting the perfect, non-sticky Sabudana Khichdi.Sola Khichdi: The only non-vegetarian item on this list is a legacy of the Dawood Bohra families from Surat. The Bohri khichdi is made with rice, an assortment of lentils (masoor, white urad, tuver), and minced meat. The ingredients are cooked with a dash of milk and fresh cream in pure ghee. It is typically served with a bowl of khurdi, a delicate meat-and-milk stock.

Tuver Dal Ni Khichdi: This simple, nourishing, and light khichdi uses tuver dal with rice to create a hot and comforting meal that’s perfect at the end of a hard day. Quick to make, you can customise the texture or thickness depending on individual tastes. Vegetables can be added if you so desire. as can spices and herbs, but it tastes just as good with sides like pickle, papad, and dahi/ raita/kadhi.

Sambhariya Rice: What happens when basmati rice meets grated coconut and freshly chopped coriander? It results in the unusual Sambhariya rice. The addition of mustard seeds, sesame seeds, curry leaves, whole red chillies, and garam masala adds a different zing to it.

Vagharela Bhaat: Ready in a jiffy, this recipe gives leftover rice a second life. The rice is combined with turmeric, chilli powder, and salt. It is then sauteed in oil to which asafoetida and mustard seeds are added. Gar- nish with chopped coriander. As a variant, add chopped onions while frying the rice.